The 1st Louisiana Native Guards was a regiment formed by wealthy free blacks of New Orleans, the ancestors of those blacks who had fought beside Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans. Many were men of means, professionals who paid for the training and equipment of a number of black regiments. At first, the services of these regiments were offered to the Confederacy with the hope that the blacks would earn respect and better treatment. New Orleans and Mobile accepted the offer but these units were never placed near the fighting.

When Butler and the Union Army occupied New Orleans in May, 1862, the black regiments immediately offered their services to the Union Army and it’s commander who accepted them into the service. On August 22, 1862, Butler published General Order, No. 63 calling on free colored militiamen of Louisiana to enroll in the Union forces, and enroll they did. By November 24, 1862, three full regiments of the Louisiana Native Guards had been mustered into the Union Army. What was unusual and not to be seen again was that when Butler accepted these units for service, he accepted them with their black officers.

Butler’s command of the occupation forces was however brief, and his replacement, Maj. General Nathaniel P. Banks, so disapproved of black officers that before long, all black officers in his command had either resigned or had been driven from the service. Although the die had been cast, preparations to raise other all black regiments in South Carolina, Kansas, Massachusetts and Rhode Island (artillery), would have to wait until the pivotal year of 1863.(see 37)

Although no known Camden County black residents served in the Louisiana regiments, the activities of these regiments received local press coverage. Their gallantry was covered in the Press while the Democrat, as expected, only stirred the fires of hatred. The October 10, 1862, edition of the Democrat reported on the execution of two Rhode Island soldiers for refusing to join with a Louisiana regiment. Under the bold headline “Horror! Horror!”, it stated: ….This regiment was ordered to be consolidated with the First Louisiana, which is, as we understand it, a Negro regiment. But the men disliked the order, and did not march to the Negro camp….Their eyes were bandaged with red handkerchiefs, and every preparation made for their execution….the signal, the sabre stroke, was for the first platoon, given, and Davis fell over backwards, as it seemed to us killed instantly….Can the mind conceive of any greater deed of horror than the murder of two Rhode Island soldiers for refusing to be consolidated with a nigger regiment!

The Copperheads were having a field day in the available media of the time as word of the Emancipation Proclamation became imminent. David Naar, Editor of the Trenton True American, and leader of New Jersey’s Copperhead southern sympathizers, printed article after article preaching racial hatred for the blacks and promulgating conspiracy theories. From the actions of New Jersey’s politicians, including Governor Joel Parker, New Jersey’s potential ability to greatly assist in the enlistment of black volunteers was dramatically hampered. It would appear that the Copperhead rantings and the fears they created did in fact have a detrimental effect on New Jersey’s movement toward military racial equality. This is evidenced by certain proposed racist legislation of 1863, which included bills forbidding black immigration into the state, banning interracial marraige, etc. None of these bills was ever passed. (see 38)

When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation he continued to maintain that “to arm the Negroes would turn 50,000 bayonets against us… that were for us.”(see 39) Lincoln retained a vision of a limited role for the black troops, “to garrison stations, and other places”.(see 40) However, in the Emancipation Proclamation publicly endorsed the use of Negroes as soldiers.(see 41) Immediately after the issuance of the decree, although diligent efforts were begun to raise colored regiments from all states under Union control, no integrated policy emerged at once. During the first three months of 1863, no standardized strategy vis-a-vis the Negro soldier was promulgated by the Lincoln Administration; grants of authority to enlist blacks into regiments were given piecemeal to the officials of four states.

Louisiana, South Carolina, Rhode Island and Massachusetts started immediately to recruit blacks both within and outside state lines by sending recruiters to the major cities of neighboring states. This caused consternation throughout the North. Each state had a quota of fighting men to supply to the federal government. Agents from one state would go to another to fill the enlistment requirements of their home state provoking complaints from other states that blacks enlisted on their own soil ought to count towards their own quotas.(see 42) The Adjutant General’s Office by Special Order 97, March 1, 1863, finally established a board to convene immediately in Washington, “to examine and report upon a system of Tactics for Colored Troops. (see 43)

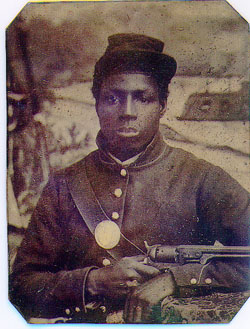

In this way, confusion and confrontation between the states was avoided. The War Department was to be in charge of all recruiting and a Bureau of Colored Troops to organize and supervise Negro units was established.(see 44) The Union Army hoped to standardize recruitment measures. As a result, the designation “U.S. Colored Troops” gradually replaced more colorful titles such as “Corps d’Afrique” and ” Zouaves d’Afrique” which had been used by Louisiana and South Carolina regiments. By using a regular army method of standardization, all black volunteers and draftees, with the exception of the Massachusetts 54th and 55th, and the Connecticut 29th, eventually became the USCT and not state regiments.

Both of these states had already put black regiments in the field and funded them completely and it was politically expedient to let them be. At the same time, Secretary of War Stanton sent authorization to the Governor of Massachusetts to recruit black troops. Within days the recruiting of the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers began, not only in that state but in the large cities of all the surrounding states, including Philadelphia.

It was here that Joseph Rice, a 22 year old farmer from Camden County, New Jersey signed up as did John W. Gaines, a 20 year old laborer from Homestead, New Jersey and Charles Hankerson, a 23 year old farmer from Burlington, New Jersey. Others, like 39 year old George Farmer, traveled north from Unionville, Pennsylvania to Readville, Massachutetts to enlist. Farmer was promoted to corporal two weeks after he was seriously wounded in the frontal attack on Fort Wagner, S.C., protecting Charleston Harbor on July 18, 1863.

After the War, Farmer settled in Camden County and is buried there in Mt. Pisgah Cemetery. Frederick Douglass began to see his dream coming true. In his March, 1863, publication, Douglass urged: “Stop not now to complain. When the war is over, the country is saved, peace is established, and the black man’s rights are secured, as they will be, history with an impartial hand will dispose of that and sundry other questions. Action! Action! not criticism, is the plain duty of this hour. Words are now useful only as they stimulate to blows. The office of speech now is only to point out when, where and how to strike to the best advantage. There is no time to delay”(see 45) Douglass urged enlistment in the 54th Massachusetts.

His two sons, Charles and Lewis, were the first two recruits from New York State to enlist in the 54th Massachusetts and their father was proud indeed. Lewis Douglass held the non-commissioned rank of Sergeant-Major of Co F. and was present in that capacity when John W. Gaines of the same company was wounded in the attack on Fort Wagner. As an incentive to enlistment monetary bounties had been offered since the beginning of the War to white recruits. By the time black enlistment became legal under the 1863 Draft Act, some of the initial states such as Massachusetts had already been offering similar bounty enticement.

For those states falling under the Draft Act however, it was not until February 24, 1864, that federal bounties of one hundred dollars paid to white enlistees were also offered to the Negro.(see 46) In July, 1864, Congress authorized African American soldiers who were free at the outbreak of the war retroactively placed on an equal pay basis with white troops; which included all New Jersey natives.

Pay equity for soldiers who had been slaves had to wait until the end of the war. This unfair treatment of the black soldiers, lower wages and no bounty contributed to their perceived second class status. Initially, inferior arms and equipment were distributed to them and they were forced to do most of the dirty work contributing to low morale, until conditions were corrected; this had to wait until after black soldiers proved themselves in battle.(see 47) *

Homestead, another name for Jordantown or Jordan’s Lawn ,located in Pennsauken Township, Camden County; Gaines is buried at Jordantown Cemetery, (See Appendix 8, No. 14).