Shortly after the initial efforts to raise black troops was remedied by the government with the creation of the United States Colored Troops, nearly all the USCT regiments, including all those organized at Camp William Penn outside of Philadelphia, were issued Springfield type or British Enfield muzzle loading rifled muskets the same as their white counterparts. Within months, the only difference in a Union soldiers appearance and armament was the color of his skin. The 79th USCT was the first black regiment to be engaged in combat: at Island Mounds, Missouri, October, 1862.

Later battles in which black soldiers participated took place at Fort Hudson and Miliken’s Bend, Louisiana. At Fort Hudson, in May, 1863, the 1st and 3rd Corps d’Afrique, (also known as Butler’s 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards), commanded by a number of black officers, charged the Confederate breastworks again and again before devastating musket fire. The plaudits they received were justly earned. At Miliken’s Bend that June, a Confederate force of between 1500 and 3000 fighting men attacked the camp of the 9th and 11th Regiments of Louisiana Volunteers of African Descent. After being driven back, the black troops rallied. Believing that if captured they would be killed, these black troops fought in frenzied hand-to-hand combat, routing the enemy.

General Elias S. Dennis witnessed the battle: “It is impossible for men to show greater gallantry than the Negro troops in this fight.” A Union naval officer who participated in a naval bombardment that helped drive the rebel army away, penned an account of the heroism of the black troops after arriving at the battle scene: “We went ashore and took a look at things. There were about 100 dead bodies on the field, about equally divided, half secesh and half negroes. The blacks fought like bloodhounds, and with equal numbers would have won the day.”(see 49) President Lincoln, made aware of the valor of black troops at Miliken’s Bend was told that ” white and black men were laying (sic) side by side, pierced by bayonets. Two men, one white and the other black, were found side by side, each with the other’s bayonet through his body.” (see 50)

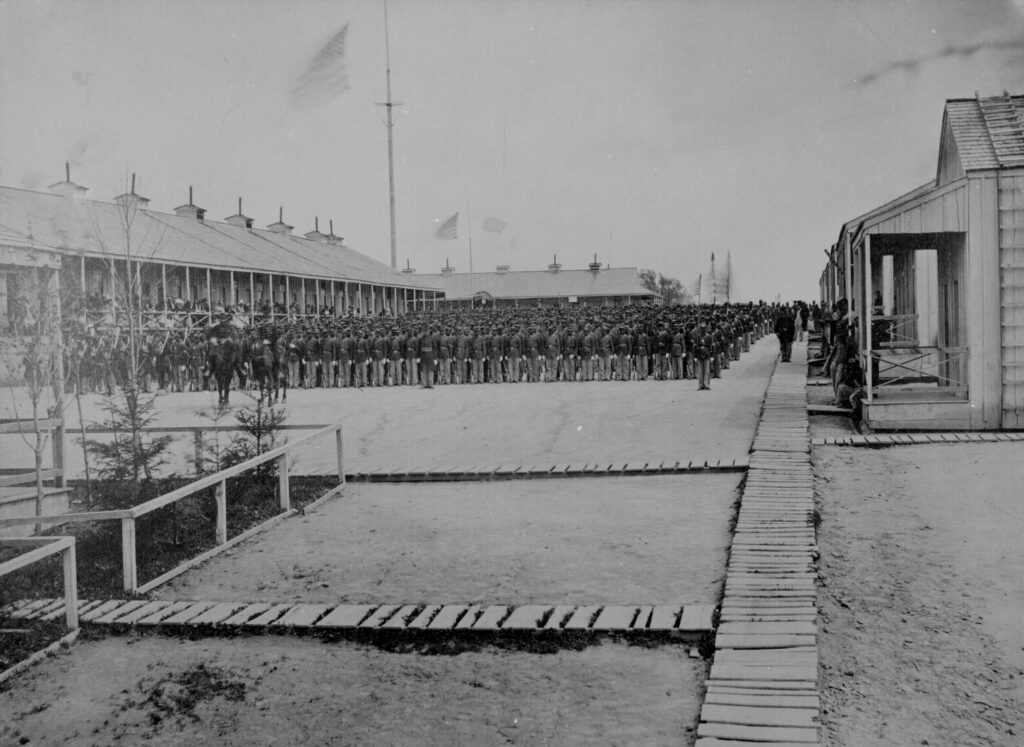

Pennsylvania began recruiting blacks in 1863 but it took nearly eighteen months before eleven regiments ( 8,612 officers and men) could be raised at Camp William Penn, in Chelton Hills near Philadelphia.(see 51) Months before, many black freemen traveled to Massachusetts and Rhode Island in order to enlist. Once other state regiments were formed, trained and sent to the front, news of recruitment was more easily spread. In Camden County, the Camden Democrat printed only negative news of the black regiments. As to the Massachusetts 54th, an article in the edition of May 30, 1863, declared, ” Gov. Andrew’s Negro Regiment has been shipped to Port Royal. That’s right – send them where there is no danger to fight – then they won’t run.”

Whether it was as a result of the Copperhead propaganda and the fears it created or a statewide political attitude, New Jersey clearly followed a course different from most other states in the Union when it came to black recruitment. While most other northern states rushed to enlist blacks, New Jersey was one of the few states where neither the governor nor a citizen’s committee ever assumed the responsibility of recruiting black soldiers in an organized or orderly fashion.(see 52)

On June 17, 1863, word was received in Philadelphia warning that General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia were moving towards southern Pennsylvania. A call to arms was issued by Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin; Philadelphia’s black population responded. A full company of 90 black soldiers under white officers was mustered into service for the emergency and marched towards Gettysburg; they were turned back when Major General Darius Nash Couch, in charge of mustering the provisional forces and homeguard levies for Pennsylvania, refused to receive them. His excuse was that Congress had only provided for enlistment of Negroes for a minimum of three years.

This action dealt a serious blow to Pennsylvania’s later attempts to raise black regiments.(see 53) Couch’s action was confirmed in the local West Jersey Press. In reporting on the actions of the Camden Rifles in the June 30, 1863 edition, the Press stated: We claim for Camden the honor of having sent the first company out of the state of Pennsylvania for the relief of this terror stricken city. In fact we are ahead of Philadelphia; for if I am correctly informed the two companies of colored Americans of African descent’ who came from Philadelphia were sent back…. As Couch was sending the black soldiers home, Major General George L. Stearns was being appointed Recruiting Commissioner for the U.S.Colored Troops in Pennsylvania. The resentment caused by Couch’s actions had an immediate demoralizing effect on the black population throughout the State because it meant a loss of eligible black soldiers for enlistment. Two per cent of Pennsylvania’s population was composed of black freemen or about 59,949 persons. Approximately 22,000 lived in Philadelphia. The total black male population of the State was 26,373.54 (see 54)

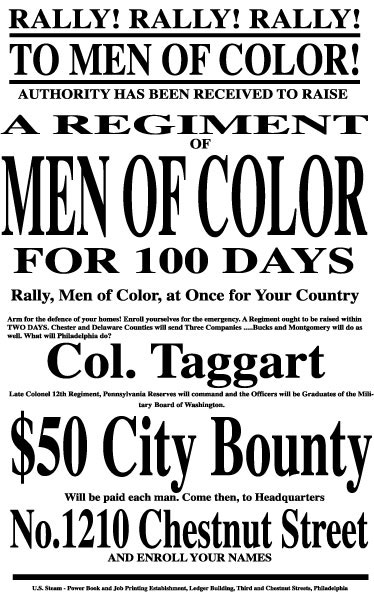

Stearns tried to counter the deep animosity created by Couch’s actions and gained the interest and support of many patriots who formed the Philadelphia Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments. This Committee recruited potential black soldiers with vigor, using posters, broadsides, newspaper advertisements and a monetary bounty to enlist. Within months of June 22, 1863, when permission was received to raise the regiments, the Committee was able to raise the first three black USCT regiments out of Camp William Penn, the 3rd, 6th, and 8th U.S.Colored Infantry. The Committee raised eleven full regiments of black troops and was instrumental in the creation of the training facility at Camp William Penn. The Committee also provided transportation for the enlistees to Camp William Penn and subsistence monies to their families.(see 55)

All black regiments organized in Philadelphia were trained at Camp William Penn. Further, the 3rd, 6th, 8th, 24th, 32nd, 41st and 127th were actually organized at Camp William Penn, while the 22nd, 25th, 43rd and 45th were organized in Philadelphia. The overwhelming majority of black Camden County residents who enlisted were in one of these eleven regiments. The photograph of Pvt. Timothy E. Shaw of Gloucester Township, a member of the 43rd USCT, taken in full uniform at Camp William Penn, is still treasured by his descendants and displayed at family gatherings. This photograph graces our cover page. Sixteen future residents of what was to become Lawnside all enlisted in those eleven regiments raised at Camp William Penn with the exception of Warner Gibbs. Gibbs was a member of Co. C, l9th Regiment USCT organized at Camp Stanton, Maryland on December 25,1863.

Others of the group such as Joseph Brewster, Benjamin F.Faucett, Joseph Gray, Garrett Patton and John C. Williams enlisted in the Union Navy.*(See Appendix No.5) Probably the most important accomplishment of the committee was the establishment of the Free Military School for Applicants for Commands of Colored Troops, located at 1210 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia. The brainchild of Thomas Webster, committee chairman, the goal was to create a facility that would produce the best possible leaders for the black regiments. Since the War Department was distinctly opposed to the appointment of black officers, the quality of leadership was important. Although about one hundred blacks did in fact hold commissions during the CivilWar, over three-fourths of them were only those in Louisiana regiments first mustered into service.(see 56)

Regardless of the early success’ of the first black regiments at Miliken’s Bend and Fort Hudson, a low opinion of the Negro as a fighting man was held by many military leaders during the early period of Negro recruiting; this was a contributory element in the continued selection of white officers to lead them.(see 57) Strict entrance examinations and personal interviews were mandatory and regarded as much harder than those imposed on applicants to command white soldiers. After completion of the course of study at the Free Military School, a successful graduate was then obligated to take and pass an examination before an examining Board at Washington or some other place’ created under the direction of Major-General Silas Casey, before a commission was offered.

Of the 1,867 students of the Free Military School examined by the Board, 1,019 were accepted and offered commissions in black regiments. Of that accepted group, only eight were from New Jersey, and one, James Mulliken, was appointed 1st Lieutenant, Co. K, 25th USCT. “Without ever becoming an actual part of the Union Army, the Free Military School of Philadelphia, grandfather of the Officer Candidate School, was geared into the Army’s machinery and played a large role in the preparation and selection of officers for colored troops.” (see 58)

Although the spirit of black enlistment was pervasive, the attitude of the Governor of the State of New York was also a barrier to the movement for racial equality in the Army. Horatio Seymour, a Democrat, with little love for Abraham Lincoln, refused to cooperate; after the passage of the Draft Act in March, 1863, New York experienced one of the most horrible non-combat tragedies of the War, in an area not threatened by invasion from the South. In July,1863, the anti-Negro feeling brought on by the draft became so strong, that bloody draft riots erupted; white mobs openly attacked blacks on the streets of New York City.

Bodies of black men, women and children killed by the mobs, were hung on the lamp-posts on Broadway.(see 59) Word of the New York draft riots spread across the nation like wildfire through articles in every newspaper. The Camden Democrat doubted the sincerity of the reports and coupled this with another harangue about the fighting qualities of black enlistees. The West Jersey Press, in response, on August 26, 1863, stated: ” It may be that among other reasons for the Democrat’s doubting negro valor is the fact that they made no resistance to the ‘friends’ of Gov. Seymour when they murdered them in New York City, and then stole the beds that orphaned negro children slept on.”

The “friends” of Governor Seymour referred to by the Press were those same “friends” of whom Frederick Douglass spoke in his autobiography. Douglass had been at Camp William Penn outside Philadelphia to assist with recruiting. He had just left to return home to Rochester, N.Y., when word came of the carnage committed on the blacks of New York City. Traveling through the city, Douglass became familiar with what was going on. In speaking of Governor Seymour, Douglass said, “…and while the mob was doing its deadly work he addressed them as ‘My Friends’, telling them to desist then, while he could arrange at Washington to have the draft arrested”.

Had Governor Seymour been loyal to his country, and to his country’s cause, in this her moment of need, he would have burned his tongue with a red hot iron sooner than allow it to call these thugs, thieves, and murderers his friends.” Governor Seymour continued to oppose any military use of black men. Even requests from President Lincoln for the Governor to raise colored regiments were denied or ignored. Seymour responded that, ” …if he could help it, New York would never arm a Negro.”

Angry citizens of New York City, many of whom were wealthy members of the new Union League, finally persuaded the War Department to accept the black units they, themselves, had organized under national authority. Thus, the 20th, 26th and 31st New York finally entered the War but Seymour had done his damage and New York which might have been a leader in black enlistment was last.(see 61)

In the end, New York, for all its wealth and resources, was only able to take credit for 4,125 black troops in the 20th, 26th and 31st Regiments.(see 62)* New Jersey also finally came around to the call for recruitment. In September, 1863, long after most other states complied, a USCT recruiting office was established at Trenton. The delay could have been the result of the Copperhead paranoia or just a general apathy towards black enlistment, but New Jersey fell into step and her black male citizens could now enlist in New Jersey and be credited to that state.

However, even with the change in attitude, the inequality continued. The enlistment bounties paid to black enlistees were considerably less than those paid to whites. Camden County was at least paying an $800 bounty to USCT recruits by early 1865.(see 63) *Practically all of the Northern states kept records of both white and black enlistees into the state armed services with the exception of New York. Only records of white soldiers were kept, and no regimental histories were apparently written about any of the three black regiments raised in New York State. While attempts were being made to enlist as many blacks as possible, the services being provided by groups such as the Philadelphia Supervisory Committees were immeasurable. At training camps all over the North, teachers provided education to the Union’s newest soldiers. Dudley Taylor Cornish, in The Union Army As A Training School For Negroes writes that the curriculum included reading and writing. Mrs. James C. Beecher, wife of the Colonel in command of the 35th USCT, organized a school and was proud that “…each one could proudly sign his name to the pay roll in a good legible hand. ”(see 64) By 1863, the black man in the United States was becoming part of the national picture.

Jobs never before available to blacks were suddenly waiting to be filled. “A new status of the Negro was taking form. In August ’62 for the first time, sworn testimony had been taken from a Negro in a Virginia court of law. Also Negro strike breakers in New York were attacked by strikers, and in Chicago, Negroes employed in the meat-packing plants were assaulted by unemployed white men. The colored man was becoming an American Citizen. (see 65) Frederick Douglass was now compelled to say, ” Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” (see 66)

Nonetheless, prejudice and racial hatred continued to affect both the North and the South. The racial tragedy provoked by the draft riots proved that no geographic area was immune to bigotry. It was one thing, most Northerners reasoned, to regard enslavement of the black race as cruel and inhumane; it was another to ask Northerners to regard blacks as their equals or welcome them as neighbors and friends. (see 67) Northern cities such as Philadelphia, with its large black population became ripe for racial unrest. Because of this unrest, early regiments stationed at Camp William Penn, including the 3rd Regiment USCT, were not allowed to march down city streets in parade uniform before going off to War. In October, 1863, however, the newly formed 6th United States Colored Troops did in fact march down Walnut, Pine and Broad streets to the cheers of the crowds. A small incident occurred when the black flag-bearer was pushed to the ground but no riot or further incidents took place.

Nine Camden County black residents were possibly among the 6th USCT when it marched through the streets of Philadelphia. Seven of them, John Briscoe, William Hall, Benjamin Hutt, Thomas Jones, Charles Manoll and John Short are all buried together at Johnson Cemetery in Camden; John Pierce is buried at Butler Cemetery, also in Camden, and Thomas Chambers is buried at Grant Cemetery in Chesilhurst. Very little else is known of these men. None of them belonged to the black veterans ‘Robeson GAR Post 51 in 1886 and not one of their names appears in the 1872 Camden City Directory.

A 1937 WPA Cemetery Project catalogued at the Camden County Historical Society does have reference to a William H. Hall whose occupation is listed as a “shys keeper”. History may not know more about these men but they fought many battles together, settled together in Camden after the War and are together in death, comrades in eternity.

Undercurrents of prejudice in Philadelphia against blacks however, continued to remain “dangerously close to the surface.” Philadelphia and New York City were not unique in their racial attitudes. Washington, D.C., the seat of federal government, also had its share of beatings and assaults upon black Union soldiers assigned to that city; many were perpetrated by white comrades-in arms.

Washington, D.C. however, was a southern city much different from Philadelphia and New York where slavery was finally abolished during the Civil War itself. Opposition to blacks as soldiers, was also not always confined to cities and camps. Many Union Army officers including General William Tecumseh Sherman, felt that blacks should be used only as laborers. When asked for an opinion on the use of blacks as soldiers, Sherman said, ” Is not a negro as good as a white man to stop a bullet? Yes: and a sand bag is better; but can a negro do our skirmishing and picket duty? Can they improvise bridges, sorties, flank movements, etc., like a white man? I say no.” (see 70)

Some government suppliers saw to it that only substandard supplies were provided to black units, and pocketed the difference in cost. A variety of fraud was committed upon black enlistees ranging from outright theft of individual pay vouchers to the disappearance of entire regimental payrolls. (see 71) Nonetheless, because the selection process to find competent white officers to command black troops included high educational and moral standards, many poor risks were weeded out beforehand and crimes such as mistreatment and theft were kept to a minimum. “Most white officers commanding black troops knew well that Northern and Southern Society had mistreated blacks, that blacks were rightly skeptical of whites, and that they must earn the trust and respect of their black soldiers if the USCT was to accomplish anything in the War.” (see 72)

There were, of course, instances wherein punishment meted out to black soldiers might have been viewed as persecution and where the punishment for a black soldier was worse than the crime. One particularly tragic incident involved the pay differential issue wherein black soldiers received less pay than their white counterparts for the same day’s work. Sgt. William Walker of the 21st USCT refused to perform his duty because he received lower pay than a white soldier of the same rank. Walker’s resistance was more passive than violent, but the military authorities arrested, tried and convicted him of mutiny. Walker was executed by military decree. Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts, a proponent of the black soldier’s rights in that state, provided the epitaph: “The Government which found no law to pay him except as a non-descript and a contraband, nevertheless found law enough to shoot him as a soldier.” (see 73)

William A. Frassanito, in his photoessay, Grant and Lee, The Virginia Campaigns 1864-1865, provides contemporary Civil War photographs taken by Matthew Brady and Timothy O’Sullivan of the execution of a black soldier during the Battle of Petersburg in Virginia. William Johnson, a black private of the 23rd USCT, was tried and convicted on June 9, 1864 by a military tribunal, of the attempted rape of a white woman at Cold Harbor, Virginia, after confessing his guilt. He was executed in front of the cameras of Brady and O’Sullivan on June 20, 1864. The event was given considerable attention in all of the newspapers of the day including Harper’s Weekly. The Harper’s Weekly reporter wrote that “considerable importance was given to the affair, in order that an example might be made more effective. Johnson confessed his guilt, and was executed within the outer breastworks about Petersburg, on an elevation, and in plain view of the enemy, a white flag covering the ceremony.”

What could have been more offensive to an individual’s right to dignity in death and more prejudicial to a race as a whole than the manner in which Johnson was put to death? In spite of such animosities, the attitude of the black soldier was positive. As Frederick Douglass had foretold, just allowing the blackman to put on the uniform and shoulder the musket would make a difference. Black men felt a sense of enthusiasm by being able to wear the blue uniform and obtain some degree of equality with the white soldier. “Yet wearing the Union uniform meant more than that: It also represented an opportunity to take an active role in freeing their families, friends and strangers whose only link was that their distant ancestors came from the same continent. ‘We are fighting for liberty and right”, exulted a black sergeant, “and we intend to follow the old flag while there is a man left to hold it up to the breeze of heaven.