There were dramatic differences between the Army and the Navy in terms of status and treatment of blacks. Prior to the Revolutionary War the intense and pervasive slave trade in the American colonies had created a fairly large maritime fleet. Ships of all types sailed the waterways of the colonies carrying tobacco, rice, indigo, wheat, sugar, rum and slaves. Cotton, which ultimately overshadowed these other goods, developed much later as a major crop. Many of the Negro slaves and freemen learned the skills of the seaman, often, not by choice, in the case of the slave.

When the Revolutionary War erupted between the colonies and Great Britain, many blacks served in the infant United States Navy in non-commissioned sea-service ranks..1 After the conclusion of the Revolutionary War it was decided by the fledgling government, that, effective January 1, 1808, some twenty years later, there would be an official cessation of the slave trade within the United States seeing an end in sight to the primary source for the labor force in the South and the availability of new slaves, caused a feverish attempt to bring more slaves into the United States before the cut-off date.

Because of this added incentive, more slaves were brought into the United States during that twenty year period than at any other similar period of time. With the conclusion of hostilities between the United States and Great Britain, many free blacks who had served in the Navy continued to maintain positions on the United States’ ships of war. During the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain free blacks readily served in the United States Navy in capacities and ranks similar to those of the previous war.2

The gravestone of Elisha Gaiter, in the cemetery of Mt. Pisgah Ave.Church, Lawnside, confirms this: “In memory of ELISHA GAITER who died May 21,1858 aged about 70 years – He was one of the crew of the U.S. ship Constitution, Cap’t Hull, in the capture of the British ship Guerriere August 19, 1812.”

The United States government determined the necessity to insure the integrity of the naval service during this period. To be sure, one of the causes of the conflict between the nations was the impressment of American sailors, both white and black, by foreign nations, especially Great Britain. The federal government soon took measures to remedy the “problem” of naval service by the passage of an act which delineated those persons who could legally serve: “That from and after the termination of the War in which the United States are now engaged with Great Britain, it shall not be lawful to employ on board any of the public or private vessels of the United States any person or persons except citizens of the United States, or persons of colour, natives of the United States.”3

A careful reading of the Act provides certain insights that cannot be overlooked. The word “citizens” is used. A Negro at this time, although free, was not considered a citizen with the same rights as a white person. The right to vote or to serve in the Army, for example, was allowed only to white citizens although in a few northern states Blacks had suffrage. The expression, natives of the United States” meant that even a free black man seeking service in the Navy had to show that his birth occurred in the United States. This Act also restricted the number of Negroes to be allowed employment in each respective crew to five percent. In this way, the management of each crew was controllable, and there would be little public outcry as to blacks taking jobs away from white seamen.4 This prohibition was to be largely violated. Regardless of this apparent discrimination policy, many free blacks sought immediate and continuous service in the navy, in both the merchant and federal fleets.

For the next forty-five years’ the black seaman’s status remained the same. He served on U.S. warships in the Seminole War and during the War with Mexico, on the majestic merchant clipper ships making trips to China, and on those ships that opened up Japan. One problem remained for the black seaman throughout this period, the problem of rank or position onboard the ship. It would take another war to correct this problem. Although the Civil War officially commenced with the Confederate attack and bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, acts of war had occurred prior to that date. After the secession of South Carolina on December 20, 1860, numerous warlike acts occurred with alarming regularity on both land and sea.

On January 3, 1861, Georgia state troops seized Fort Pulaski. The U.S. steamer, Star of the West while flying the U.S. flag was fired upon by Confederate troops as she attempted to enter Charleston harbor and relieve Fort Sumter. Also, many U.S.warships were seized by the Confederate Navy such as the U.S.Revenue schooner, Henry Dodge, seized off the coast of Texas as that state joined the Confederacy on March 2, 1861.5 Prior to the official declaration of war, the role of the U.S. Navy was to protect U.S. interests and citizens abroad; at the same time, U.S. warships were actively seeking to suppress the Africa slave trade as it affected the United States.

In 1859 and 1860, the U.S.S. Portsmouth, captured two slave ships with “contraband bound for the Americas .6 Slaves were considered “contraband” whether they were on board a ship or in a slave-holding state of the Union. Although many U.S. warships participated in similar slave ship captures, this research deals only with those ships on which Camden County black residents served as sailors. One who did so was N. Buck Hornelson;* See Appendix I-Gravesite #88 Mt. Peace Cemetery, Lawnside, who served on the U.S.S. Portsmouth, which on September 21, 1859, captured the American slave ship Emily at Loango, Africa, and on May 6, 1860, took the slaver Falmouth off Port Praya.7

After the outbreak of wartime hostilities, ships such as the Portsmouth, and others, began to actively engage in combat operations and served throughout the entire Civil War. The status of “contraband” negroes immediately changed when shots were fired at Fort Sumter. Gideon Wells, President Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, recalled all U.S. warships from foreign ports, 42 commissioned ships in all. Two days after the “surrender of Fort Sumter on April 13, 1861, when President Lincoln called for the enlistment of 75,000 volunteers, he also declared a blockade of all southern ports from South Carolina to Texas; shortly thereafter the coasts of Virginia and North Carolina were also included. The need for manpower to staff these warships, already in commission and those to be constructed, was at an all time high.

The answer came in the form of “contraband” – those freed and runaway slaves who flocked to Union ships in great numbers beginning in 1861. In most instances they were immediately employed. On September 20, 1861, Wells declared that “contrabands” could be hired as sailors and compensated for their labor. However, they were allowed no higher rating than “boy” at a rate of $10 per month and one ration per day. This pay scale and classification applied only to “contrabands” and not to freemen. 8 Wells was aware of the previous employment of black sailors on U.S. warships and noted, ” a number of able blacks were enlisted on the ships as powder monkeys and coal passers.” (see 9)

“Boys” or apprentices formed the lowest ranks in the Navy. There were 3rd, 2nd and 1st class boys who received $8, $9 and $10 respectively. Freemen could attain any rating short of a commission, but there were exceptions. Some freemen attained the technical position of pilot – the equivalent of a commissioned officer with a rate of pay of about $250 per month. As the men-of-war began to fill with “contraband” negroes, the Navy appeared to have a surfeit of manpower. Ships had “boys” of each class on board performing a myriad of tasks. Indeed, the gravestones of Osceola Butler,*See Appendix I, Gravesite #34, Mt. Peace Cemetery, Lawnside, and John Anderson,** See Appendix I, Gravesite #__, Johnson Cemetery, Camden, read “lst Class Boy – U.S.N.” and “2nd Class Boy – U.S.S. Satellite, respectively.

Black seamen made extremely important contributions to naval intelligence. “Indeed, at times, charts were changed, naval flotilla formations altered, areas entered, and assaults postponed on the basis, very largely, of data supplied by Negroes.”10 A major expedition which sought to approach Vicksburg, Mississippi from the rear, in an effort to cut off Confederate supplies, was undertaken as a consequence of “information obtained from a Negro.”11 This reliance upon the information of a black “contraband” was of extreme importance because of the magnitude of the Union offensive. The success of the Union Army and Navy at Vicksburg would not have been possible without information so provided by the Negroes who were members of the crews and who flocked to the Yankee lines from within Mississippi’s heart.12

Once the Department of the Navy realized the usefulness of these “contrabands” it rescinded previous orders and allowed them to ship out in ranks as high as “landsman” (just above 1st class boy); they were also eligible for promotion to coal-heaver, fireman, ordinary “seaman and seaman.13 Such changes gave “contrabands” the same status and the same rights as freemen in the naval service. The warships of the United States Navy during the Civil War were arranged into blockading squadrons, comprised of all manner of seagoing craft, including battle-ships, rams, troop transports and support vessels.

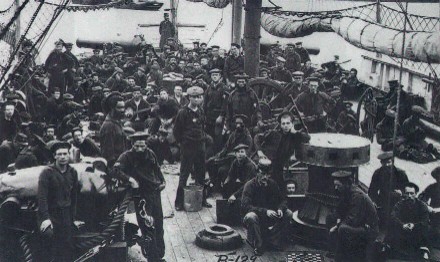

As we have seen, soon after the outbreak of hostilities, U.S. warships began to take on qualified free blacks as part of the crews. The U.S.S. New Hampshire, had a total crew of 969 of which the total number of black seamen of all ranks was 242.14 The increased percentage was in direct violation of a number of Naval Acts but no one seemed to mind. Sometime after the end of the Civil War the Superintendent of Naval Records estimated that the Civil War Navy was approximately one-quarter Negro – about 29,511 men.15 In addition, he also calculated that “at a minimum about 3000 Union Negro Sailors died from disease and enemy action.”16

Because of the great influx of blacks into the federal naval service and their great contributions to the cause of the Union, Congress returned the favor by passing laws to help them and their white compatriots. On July 17, 1862, an act of Congress was established which provided “every officer, seaman, or marine, disabled in the line of duty, shall be entitled to for life, or during his disability, a pension from the United States, according to the nature and degree of his disability, not exceeding in any case his monthly pay.”17

This Act automatically granted valid, new rights to all men who served including free black sailors and former “contraband”. Additionally, Secretary of the Navy Wells notified flag officers of a bill authorizing the President to appoint annually, three midshipmen to the Naval Academy from the enlisted “boys” of the Navy.18 Blacks could now become commissioned officers in the United States Naval Service. However, the first Negro enrollment in the U.S. Naval Academy did not take place until after the Civil War had been over for some time. James Henry Conyers enrolled on September 11, 1872. He did not graduate, leaving the Academy on November 11, 1873 for an unknown reason. 19

Many problems were encountered during the basic research for this study. It was difficult to determine which Civil War sailors were of African-American descent, and to confirm the names of those who were residents of Camden County prior to the commencement of the War. The Army Service kept better records in regard to the races. Many states, designated those black members of the United States as Colored Troops or some other identification such as black regiments of their respective states. This attention to color was not true in the Navy; northern states failed to provide similar types of designation to blacks who joined the Navy. Massachusetts, which provided the largest number of men for the Union fleet, published one and one-half volumes of names of each of her Civil War sailors and did not distinguish Negro from white. 20 What follows is an attempt to identify and confirm the service of those sailors of African-American descent, who lie buried in Camden County.

Rubbings were taken from the gravestones which were then plotted on a map; the names thus obtained were then confirmed against existing state and federal records. The warships aboard which these men served were verified in official Navy Registers and a brief record of the service of these ships has been set forth. An appendix permits easy identification and location of any confirmed veteran listed in the Alphabetical Appendix. A further reference to A Chronology of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1965 , by David M. Cooney, will provide additional information about U.S. warships other than that provided here.

Nonetheless, there have been few, if any, historical studies of the role of the Negro in the Union Navy during the Civil War, although books are often written on the contributions of black soldiers during the War, the role of black sailors has been largely neglected. [Herbert Aptheker], a noted historian on black history, has referred to their role: “…[black sailors] constituted some twenty-five percent of the total personnel, they performed all duties required of sailors aboard mid-nineteenth century men-of-war, they behaved well, at times, with conspicuous gallantry, under fire, and their contribution, particularly in terms of information concerning the enemy’s potential, disposition, and terrain, was invaluable. The role of the Federal fleet in determining the outcome of the Civil War long has been recognized as decisive. The role of the Negro members of that fleet was of primary importance.21

Navy warships acted as guardians over troop transports and war zones; therefore often no combat actions are listed for such service. However, I have listed all known ships which have been confirmed as having black Camden County sailors in service. The name of the seaman and his rank is given if known. Since “boy” was the lowest rating available it probably indicates that the individual entered naval service as a “contraband” enlistment. The rankings below commissioned officers, in descending order, were: seaman, ordinary seaman, fireman, coal-heaver, landsman and boy 1st, 2nd and 3rd class.

Many gravestones in Camden County’s black cemeteries proudly signify the rank achieved and the warship on which the veteran served. Other naval positions such as steward, cook, etc., were actually landsman ratings wherein the sailor was doing a specific duty while aboard ship. A landsman was an inexperienced seaman. With the passage of time on board ship and experience at a particular duty, higher ratings were attained. The following attempts to set forth the specific warship or vessel confirmed as part of the Union Navy together with a listing of black Camden County crewmen known to have served on that ship. For each ship, a chronological list of the naval actions engaged in by that vessel is given.

The sailors are listed by name, cemetery and gravesite location. A number of those seaman interred at Johnson Cemetery located in Camden City do not have gravesite locations. Although many veterans were confirmed to be buried at Johnson Cemetery during a 1978 study, their gravestones have been removed and exact location of their graves is now impossible. Thus, I pay tribute to those who served “with conspicuous gallantry.” When reference is made to the “rate” of a ship or vessel, it refers to the tonnage of the type of ship. For example, a paddle-wheeler steam ship such as the U.S-.S. Powhatton, was classified as First Rate. This means that the tonnage of the Powhatton was at least 2,400 tons and upwards. Below this tonnage was either Second, Third or Fourth Rate. The application of rate applied to sailing vessels, screw steamers, paddle-wheelers and iron-clad steamers.

Many larger warships acted in the capacity of receiving ships which were actually supply ships, and training vessels for new sailors and never engaged in combat. Confirmation as to combat action was obtained from the Register of the Commissioned, Warrant, and Volunteer Officers of the Navy of the United States to January 1, 1864,(Washington:1864), and A Chronology of the U.S. Navy 1775-1965, by David M. Cooney (New York:1965).

U.S.S. Satellite: listed in the Register as a steamer.

Sailors: John Anderson, 2nd Class Boy – Johnson Cemetery Actions: July 27. 1862, captured the schooner J.W. Sturges, in Chippoak Creek, Va. August 15. 1862, covered the withdrawal of McClellan’s Army from Harrison’s Landing. May 21. 1863, captured the schooner Emily off the mouth of the Rappahannock River, Va. August 17. 1863, captured the schooner Three Brothers, in the Great Wicomico River, Md. August 23. 1863, U.S.S. Satellite captured by a Confederate boat expedition off Windmill Point on the Rappahannock River, Va. August 25. 1863, U.S.S. Satellite destroyed by Confederate force because they lacked the fuel and spare parts necessary to operate it.

U.S.S. Powhatton: listed in the Register as a First Rate Paddle-Wheeler with 21 guns and the Flagship of the West India Squadron.

Sailors: William Floyd, Seaman – Johnson Cemetery Samuel F. Brown, Landsman – Mt. Peace #51 Actions: June 26. 1861, along with other vessels, set the Union blockade at Mobile, Ala. June 29. 1861, captured the schooner Mary Clinton attempting to run the blockade near Southwest Pass, Mississippi River. August 13. 1861, recaptured the schooner Abby Bradford off the mouth of the Mississippi River. April 19. 1863, captured the schooner Major E. Willis near Charleston. May 16. 1863, captured the sloop C. Rotereau off Charleston.

U.S.S. Alleghany listed in the Register as a Third Rate Screw Steamer with 10 guns and which acted as a Receiving Ship at Baltimore, Md. Sailors: John H. Blake, Steward – Johnson Cemetery Samuel F. Brown, Landsman – Mt. Peace #51 Lewis Christmas, Landsman – Mt. Peace #93 Frederick Jones, Landsman -Mt. Pisgah #1 John W. White, Landsman – Mt. Pisgah #8 Actions: None

U.S.S. Kansas: listed in the Register as a Forth Class Screw Steamer with 8 guns and being part of the North Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Samuel Bleem, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery Actions: May 15. 1864, captured the British blockade-runner Tristam Shandy east of Fort Fisher.

U.S.S. South Carolina: listed in the Register as a Third Class Screw Steamer with 8 guns and being part of the South Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Samuel Gillen, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery Norman Simmons, Landsman – Mt. Peace #33 Actions: July 9. 1861, seized and destroyed the schooner Tom Hicks off Galveston,Texas. July 12. 1861, captured the Confederate ship T.J. Chambers off Galveston, Texas. August 3. 1861, engaged Confederate batteries at Galveston, Texas. September 11, 1861, captured Soledad Cos off Galveston, Texas. October 4. 1861, captured the Confederate schooners Ezilda and Joseph H. Toone off South West Pass of the Mississippi River. October 16 1861, captured the schooner Edward Barnard at South West Pass, Mississippi River. December 11. 1861, captured the Confederate sloop Florida off the Timbalier, La. lighthouse. February 19. 1862, together with the U.S.S.Brooklyn, captured the steamer Magnolia in the Gulf of Mexico. August 27. 1862, destroyed the abandoned schooner Patriot, near Mosquito Inlet, Florida. March 29. 1863, captured the schooner Nellieoff Port Royal, So. Car. April 12. 1864, a boat party captured the British blockade-runner Alliance aground on Daufuskie Island, So.Car.

U.S.S. North Carolina: listed in the Register as a Third Class ship with 6 guns acting as the Receiving Ship at New York.

Sailors: Solomon Clark, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery David Simons, Landsman – Mt. Peace #47 Thomas Perkins, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery Actions: None

U.S.S. Princeton: listed in the Register as a Third Class Screw Steamer with no armament acting as the Receiving Ship at Philadelphia.

Sailors: Milton Dix, No Rate – Johnson Cemetery John P. Fitzgerald, Landsman – Butler #4 Joseph Gray, No Rate – Mt. Pisgah #11 George Harding, Landsman – Mt. Peace #39, Wm.H.Hegamin, Ord. Seaman – Mt. Peace #75, Samuel Jackson, Landsman – Butler Cemetery, Lewis Christmas, Landsman – Mt. Peace #93, Asa Pierce, Landsman – Mt. Pisgah #19 Charles Price, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery John H. Preston, Landsman – Mt. Peace #67, Henry Sparrow, Landsman – Mt. Peace #95, Richard W. Thomas, Landsman – Johnson. Actions: None

U.S.S. Mingoe: listed in the Register as a Third Class Paddle-Wheeler carrying 10 guns being built at Bordentown, N.J. as of January 1, 1864.

Sailors: William A. Drake, Steward – Johnson Cemetery Actions: None

U.S.S. Crusader: listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Screw Steamer with 7 guns as part of the North Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: John H. Blake, Steward – Johnson Cemetery Actions: May 23. 1860, (Before the outbreak of War), captured the slaver Boota with 500 slaves aboard off the coast of Cuba. July 23,1860, captured the slaver William R. Kirby at Aquila, Cuba. She had been deserted by her crew and 3 African boys had been left aboard. August 14. 1860, captured an unarmed slave brig off Cuba. May 20. 1861, captured the sloop Neptune near Fort Taylor’ Florida. April 18. 1862, a landing party and Army troops attacked Edisto Island, S.C. June 21. 1862, a joint Army-Navy expedition ascended to Simmons Bluff, S.C., and destroyed a Confederate encampment. February 20. 1863, captured the schooner General Taylor, in Mobjack Bay, Va. May 22. 1864, captured the schooner Isaac L. Adkins off the Severn River, Md.

U.S.S. Marlange: Not listed in Register.

Sailors: Alexander Lotley, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery

U.S.S. New Hampshire: listed in the Register as a First Class Sailing Ship with 10 guns fitted as a Store Ship at Portsmouth, New Hampshire as of January 1, 1864.

Sailors: James H. Duckery, Landsman – Mt. Peace #42 Garrett Patten, Landsman – Mt. Zion #19, John W. White, Landsman – Mt. Pisgah #8 Lewis Christmas, Landsman – Mt. Peace #93. Actions: None

U.S.S. Louisiana listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Screw Steamer with 5 guns and as part of the North Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Joseph Gibson, No Rate – Johnson Cemetery Actions: October 5. 1861, two boats from the Louisiana destroyed a Confederate schooner being fitted out as a privateer at Chincoteaque Inlet, Va. October 7. 1861, captured the schooner S.T. Carrison near Wallops Island, Va. October 27. 1861, a boat expedition surprised and burned 3 Confederate vessels at Chincoteaque Inlet, Va. Februarv 7. 1862, took part in the capture of Roanoke Island, Va. February 10. 1862, along with other warships, destroyed the fort and batteries at Cobb’s Point, N.C. September 6. 1862, supported Union troops in repelling Confederate attack on Washington, D.C. A boat crew captured the

June 16. 1864, along with other ships captured the Confederate schooners Iowa, Mary Emma, and Jenny Lind. December 24. 1864, the powder ship Louisiana was exploded 250 yards from Fort Fisher, although the explosion had almost no effect on the Fort. Thus, Union plans to assault a weakened position were frustrated.

U.S S. Brandywine: listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Frigate with 1 gun acted as a Store Ship at the Norfolk Navy Yard.

Sailors: Peter Heath, Landsman – Mt. Peace #35, Frederick Jones, Landsman – Mt. Pisgah #1, Samuel F. Brown, Landsman – Mt. Peace #51 Actions: None

U.S.S. Connecticut: listed in the Register as a Second Class Paddle-Wheeler with 11 guns and as part of the North Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Isaac W. Riley, Landsman – Mt. Pisgah #20 Actions: November 17. 1861, captured the British schooner Adeline loaded with military stores, off Cape Canaveral, Florida. January 17,1862, captured the British blockade -runner, Emma, off the Florida Keys. September 22. 1863, captured the British blockade-runner Juno off Wilmington. December 20. 1863, captured the British blockade-runner Sallie off Frying Pan Shoals, N.C. March 1. 1864, captured the British blockade-runner Scotia off Cape Fear. May 9. 1864, seized the British blockade-runner Minnie at sea.

U.S.S. Wabash: listed in the Register as a First Class Screw Steamer with 48 guns and as part of the South Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Lewis Christmas, Landsman – Mt. Peace #93 Actions: August 26. 1861, became part of the first combined amphibious operation of the Civil War under Major General Butler. September 29. 1861, became the Flagship for a Union expedition to Port Royal, S.C., which comprised 77 vessels – the largest U.S. fleet ever assembled up to that time. March 11. 1862, a landing party occupied St. Augustine, Fla. April 11. 1862, participated in the surrender of Fort Pulaski, Ga.. April 19. 1864, was attacked by a Confederate torpedo boat called the David. The David was taken under fire by the Wabash and was forced to turn back because of the heavy swells which threatened to swamp it.

U.S.S. Juniata: listed in the Register as a Second Class Screw Steamer with 9 guns.

Sailors: Williams S. Peters, Cook – Johnson Cemetery Actions: April 29. 1863, captured the schooner Harvest at sea. June 12 1863, captured the schooner Fashion off the coast of Cuba. July 12. 1863, seized the British blockade-runner Don Jose at sea.

U.S.S. Daylight: listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Screw Steamer with 8 guns and as part of the North Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Henry Robinson, Ord. Seaman – Mt. Peace #29, Richard Thomas, Steward – Johnson Cemetery, Osceola Butler, 1st Class Boy – Mt. Peace #34 Actions: July 14. 1861, initiated the blockade of Wilmington, N.C. August 26. 1861, recaptured the brig Monticello in the Rappahannock River. October 10. 1861, silenced a Confederate battery attacking the American ship John Clark anchored in Lynnhaven Bay, Va. April 26. 1862, participated in the surrender of Fort Macon, N.C. October 30. 1862, captured the schooner Racer off New Topsail Inlet, N.C. November 4. 1862, forced the British blockade runner Sophia aground and destroyed her near Masonboro Inlet, N.C. December 3. 1862, captured the British blockade-runner Brilliant off Wilmington, N.C. December 8. 1862, captured the sloop Coquette off New Topsail Inlet, N.C. January 21 1863, destroyed a blockade-runner off New Topsail Inlet, N.C. .December 25. 1863, landed troops at Bear Inlet,N.C. to destroy 4 extensive salt works. January 3. 1864, together with other ships destroyed the steamer Bendigo aground at Lockwood’s Folly Inlet ,S.C.

U.S.S. Jamestown: listed in the Register as a Third Class Sloop with 22 guns and assigned to the East Indies.

Sailors: Richard Thomas, Steward – Johnson Cemetery, Richard W. Thomas, Landsman – Johnson Actions: August 5. 1861, burned the Confederate prize bark Alvarado near Fernandina, Fla. August 31. 1861, captured the British blockade running schooner Aigliurth off the Florida coast. December 15. 1861, captured the Confederate sloop Havelock near Cape Fear, N.C. May 1. 1862, captured the British blockade-runner Intended off the coast of N.C. May 26. 1864, the U.S. Minister to Japan requested that Captain Cicero Price bring the Jamestown to Kanagawa, because the Japanese had threatened to stop trade at that port.

U.S.S. Seneca: listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Screw Steamer with 4 guns and as part of the South Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: John H. Preston, Landsman – Mt. Peace #67 Actions: November 5.1861, together with other ships engaged and dispersed a small Confederate squadron and fired on Fort Beauregard and Fort Walker. November 20. 1862, captured the schooner Annie Dees off Charleston. July 18. 1863, participated in the second attack on Fort Wagner, Charleston Harbor. Fire from the ships supported troop advances on the fort, but as the sun set the bombardment stopped and the troops were repelled with heavy losses. September 22. 1863, a landing party from the ship destroyed a salt works near Darien, Ga.

U.S.S. Vermont: listed in the Register as a Third Class Sailing Ship with 18 guns and as part of the South Atlantic Squadron acted as a Store and Receiving Ship.

Sailors: Samuel F. Brown, Landsman – Mt. Peace #51 Actions: None.

U.S.S. Cimerron: listed in the Register as a Third Class Paddle-Wheeler with 10 guns and as part of the South Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: William Jones, Seaman – Mt. Pisgah #13 Actions: July 31. 1862, conducted counter-battery fire with Confederate batteries at Coggin’s Point, Virginia. Two Army transports were sunk in the action. September 8. 1862, became part of a “Flying Squadron” under Commodore Wilkes with orders to seek out and capture commerce raiders, C.S.S. Alabama and Florida. May 29. 1863, captured the blockade-runner Evening Star off Wassaw Sound, Ga. September 13. 1863, captured the British blockade-runner Jupiter in Wassaw Sound, Ga. April 21. 1864, a landing party destroyed a rice mill and 5000 bushels of rice stored at Winyah Bay, S.C.

U.S.S. Aries: listed in the Register as a Third Class Screw Steamer with 7 guns as part of the North Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Samuel F. Brown, Landsman – Mt. Peace #51 Actions: March 28. 1863, the British blockade-running steamer Aries seized the U. S. S. Stettin off Bulls Bay. December 6. 1863, captured the damaged British steamer Aries at the mouth of Cape Fear, N.C. Januarv 11. 1864, chased the blockade-runner Ranger aground and burned her at Lockwood’s Folly Inlet, S.C.

U.S.S. Potomac: listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Frigate with 32 guns and as the Storeship of the West Gulf Squadron.

Sailors: Isaiah Jordan, Coal Heaver – Mt. Peace #28. Actions: July17-18. 1862, a landing party of 40 marines and sailors conducted an expedition up the Pascogoula River, Miss.,to destroy Confederate ships loading cotton. They disrupted Confederate communications but were turned back by cavalry before reaching the ships.

U.S.S. St. Lawrence, listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Frigate with 12 guns as the Ordinance Ship of the North Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Isaac Major, Seaman – Mt. Zion #3 Actions: July 16. 1861, captured the British blockaderunner Herald, bound from Beaufort, N.C. to Liverpool. July 28. 1861, sank the Confederate privateer Petrel, off Charleston.

U.S.S. Portsmouth: listed in the Register as a Third Class Sloop with 20 guns as part of the West Gulf Squadron.

Sailors: N.Buck Hornelson, Landsman – Mt. Peace #88 Actions: February 1. 1862, captured the steamer Labuon at the mouth of the Rio Grande River. February 20. 1862, captured the sloop Pioneer off Boca Chica, Tex. Apri1 24. 1862, part of the Union fleet under Flag Officer Admiral David Farragut when it engaged the Confederate flotilla at New Orleans.

U.S.S, Sebaao, listed in the Register as a Third Class Paddle-Wheeler with 10 guns and as part of the South Atlantic Squadron.

Sailors: Thomas Perkins, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery Actions: May 17. 1862, part of the fleet expedition with troops to capture Confederate vessels to prevent destruction.

U.S.S. Ohio: listed in the Register as a Third Class Ship with 17 guns and as the Receiving Ship at Boston.

Sailors: William T. Martin, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery Actions: None

U.S.S. Ticonderoga: listed in the Register as a Second Class Screw Steamer with 20 guns and being ready for sea at Philadelphia as of January 1, ;864.

Sailors: Henry C. Morgan, Landsman – Johnson #12 George H. Watson, Seaman – Johnson Actions: None.

U.S.S. Calina: not listed in the Register as of January 1864.

Sailors: Amos W. Nash, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery Actions: None

U S S Hornet: not listed in the Register as of January 1, 1864.

Sailors: John W. White, Landsman – Mt. Pisgah #8 Actions: None

U.S.S. Chattanooga: listed in the Register as a First Class Serew Steamer with 8 guns under construetion at Philadelphia as of January 1, 1864.

Sailors: John W. White, Landsman – Mt. Pisgah #8 Actions: None

U.S.S. Yantic: listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Screw Steamer with 5 guns under construction at Philadelphia as of January 1, 1864.

Sailors: John W. Williams, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery. Actions: None

U.S.S. Independence: listed in the Register as a Third Class Frigate with 50 guns and as the Receiving Ship at the California Navy Yard.

Sailors: Sheppard Pitts, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery ,Richard W. Thomas, Landsman-Johnson Cemetery Actions: None

U.S.S. James S. Davis: listed in the Register as a Fourth Class Bark with 4 guns and as part of the East Gulf Squadron.

Sailors: Adam Russ, Landsman – Johnson Cemetery Actions: None

U.S.S. Hartford: listed in the Register as a Second Class Screw Steamer with 28 guns and as part of the West Gulf Squadron.

Sailors: John Lawson, Landsman – Mt. Peace Cemetery Actions: Januarv 9. 1862, Flag Officer David G. Farragut assumed command of the West Gulf Squadron. His flagship was the U.S.S. Hartford. March 19. 1863, under the command of Rear Admiral Farragut- passed the Confederate batteries at Grand Gulf, Miss. enroute up the Mississippi to Vicksburg; engaged the batteries, suffering 8 casualties.

Farragut had been raiding the river banks as he moved north. April 1. 1863, began the blockade at the mouth of the Red River, La. July 9. 1863, Port Hudson, La., surrendered to Union forces, ending a prolonged attack begun when Rear Admiral Farragut first passed upstream to Vicksburg.

With the fall of Port Hudson, the Union gained control of the Mississippi River, thereby cutting the Confederacy in two. August 5. 1864, Rear Admiral David Farragut led a squadron of 18 ships into Mobile Bay, encountering a Confederate flotilla under Rear Admiral Franklin Buchanan. The Battle of Mobile Bay followed.

Farragut used the same technique which he had employed at New Orleans, lashing the smaller vessels to the sides of the larger screw steamers to protect them from the guns of Fort Morgan. In the heat of battle, the U.S.S. Tecumseh struck a torpedo and sank almost immediately with a loss of 80 officers and men. The fear of more torpedoes caused the entire Union squadron to stop in the narrow channel under the guns of Fort Morgan.

Admiral Farragut, aloft in the rigging of his flagship Hartford, then gave his famous order, ” Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” The Hartford proceeded leading the squadron through what, today, would be called a minefield. Although the torpedoes could be heard striking the Hartford’s hull, none exploded; as Farragut had reasoned, they had become defective from prolonged immersion.

Thus, the Union squadron entered Mobile Bay in spite of its strong outer defenses. Admiral Buchanan attempted unsuccessfully to ram the Hartford with the iron-clad Tennessee. Hartford, faster and more maneuverable, avoided contact and returned fire. Farragut then ordered the destruction of the Tennessee by gunfire or ramming; the Hartford rammed the Tennessee and fired a broadside into her from a range of less than 15 feet. The Tennessee, surrounded, hoisted the white flag and surrendered. The Confederates lost 12 killed and 20 wounded; the Union squadron paid a higher price, 132 killed and 170 wounded.

John Lawson made a momentous contribution to the Union cause during this encounter: and was awarded the Medal of Honor for his action. He was one of only 327 Civil War sailors and Marines to be so honored. Lawson was born in 1837. Although his residence was officially listed as Pennsylvania, Lawson’s family lived in New Jersey; and upon his death, he was buried at Mt. Peace Cemetery in Lawnside. Lawson held the rank of Landsman on board the U.S.S. Hartford and participated in the attacks against Fort Morgan, several rebel gunboats and the Confederate ramming ship Tennessee during the Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864. Lawson was wounded in the leg and thrown violently against the side of the ship when an enemy shell which killed or wounded the six-man crew whipped on the berth deck.

Upon regaining his composure, he immediately returned to his station and, although urged to go below for treatment, steadfastly continued his duties throughout the remainder of the action. Under General Order 45, December 31, 1864, John Lawson was awarded the U.S. Naval Medal of Honor for heroism in the Battle of Mobile Bay. (See Appendix) 22

In addition to those black sailors listed above, there are others for whom no ship assignment could be determined. On the other hand, a review of the pension records at the National Archives indicates that many of the sailors listed above were credited with service on ships other than those named on their tombstones. For example, Benjamin F. Faucett, buried at Mt. Zion Cemetery (#18), has only the designation “Landsman” listed on his memorial.

The official pension records show that Faucet served on at least four warships during the Civil War, the U.S.S. Vandalia, T.A. Ward, Princeton, and Wabash. Appendix III which follows provides that information which was obtained from the National Archives for those persons so identified. Information not appearing in the text may be found in the Appendices, including names and other pertinent family information.