The 8th was not the only black regiment to suffer losses at Olustee, the 35th USCT and the Massachusetts 54th suffered with the 8th. Of those black soldiers engaged at the battle of Olustee, Camden County claims at least 11 members of the 8th USCT whose gravesites have been identified. The West Jersey Press published a list which included the names of others whose gravesites have not yet been located. After the black regiment’s initial success’, local newspapers such as the West Jersey Press began to list the black soldiers names together with those of the white soldiers.

The edition of August 10, 1864, lists one of the 10 men,”William H. Jones col’d” of the City of Camden as drafted. The regimental roster indicates that Jones was a member of the 8th USCT organized at Camp William Penn as of December 4, 1863. The 8th participated at Olustee, in the Battles of Petersburg, Chaffin’s Farm and New Market Heights in Virginia. It was part of the Appomattox Campaign in March, 1864, they pursued General Robert E. Lee and his army to the end of the War and was present when Lee surrendered to Grant on April 9, 1865.

Other members of the 8th USCT whose remains have been identified were George Baley, James Burk, Robert Guster, Daniel Derry, John Green, Alfred Johnson, Henry Jones, Thomas Schenck, John Henry Wells and George Johnson. George H. Stewart, while not originally from Camden County, settled here after the War and is buried at Johnson Cemetery. Stewart, a member of Co.G, 54th Massachusetts, was a 35 year old seaman from Watertown, New York. He was captured at the Battle of Olustee and subsequently exchanged on March 4, 1865 only to be hospitalized at the General Hospital at Alexandria, Virginia for disease contracted while held prisoner.

By the time Grant had taken over command of the Union forces, the tide was turning for the North. A plan was devised whereby the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia would be captured and the War ended. While one Union force was to keep Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia busy, another force would cross over the Peninsula and attack Richmond from the south. Only the city of Petersburg stood in the way.

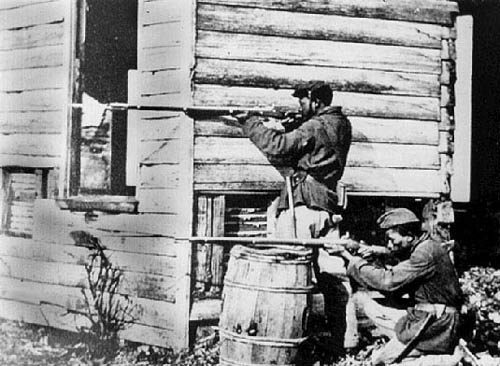

Although the North had a strategic opportunity to capture Petersburg quickly, that opportunity was lost because of delay and Grant determined to lay siege to the area. Black regiments were transferred to the Petersburg area to become part of the siege army and to help dig the trenches that were to become part of an underground way of life. After months in the trenches a plan was brought forth by General Ambrose E. Burnside to dig a tunnel under the Confederate lines, fill the tunnel with explosives and ignite them. His plan was approved by the High Command and Pennsylvania soldiers who had worked in the coal mines were assigned to dig the tunnel.

When the explosion occurred, the Union forces were to charge the Confederate lines. On July 30, 1864, the mine was ignited, the Battle of the Crater began. Although black regiments had initially been chosen to lead the assault, orders came to hold these units in abeyance. White troops led the attack but by the time they were sent in, the rebels had regrouped and laid heavy fire on the attackers. When the black regiments, part of General Edward Ferrero’s 4th Division, IX Corps, finally went into the Crater, they had to fight their way over the dead and dying bodies of their white comrades. A multiplication of military errors had already occurred by the time the black regiments were ordered to attack, and the order was so ill-advised and so poorly executed that they were butchered by the hundreds.

The black 4th Division suffered 1,327 casualties compared to 654 in the 1st, 832 in the 2nd and 659 in the 3rd. The total killed in the colored brigades was 195, compared with 227 killed in the three white divisions combined.(see 93) Nearly one in every eight soldiers at Petersburg was black. The largest number of Camden County black soldiers participated in the Battle of Petersburg and the siege which preceded it. Nine separate regiments including the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, l9th, 22nd, 39th, 43rd and 127th all had a substantial roster from Camden County: approximately 86 participants have been identified by gravesite.

Of Smiley’s list, Joseph Brewster, Isaiah Grose, William Jackson and John L. Stephens all belonged to the 22nd USCT. Andrew Beckett and Thomas White (misspelled Wright), belonged to the 127th USCT. Cubit Moore and Timothy Shaw belonged to the 43rd USCT. Warner Gibbs, also listed as one of Smiley’s forty-six who left Lawnside to go to war, was a member of the l9th USCT organized at Camp Stanton, Maryland, which state took credit for his enlistment.

Many of the men who went to war together and survived tended to live near each other after the war. All of the Camden County members of the 6th USCT appear to have lived in the same area of Camden City and all but one are buried in the same cemetery-Johnson Cemetery. Among the members of the 8th USCT, George Baley, James Burk, Robert Guster and Daniel Derry all were buried at Mt. Peace Cemetery, Lawnside; the remains of John Green, Alfred Johnson, Henry W. Jones, William Jones, Thomas Schenck and Joseph Henry Wells lie in Johnson Cemetery, Camden City.

All of those who were identified as residents of Lawnside are buried in one of the three local cemeteries. Timothy Shaw was interred at Davistown Cemetery, Gloucester Township. These men who had seen death and destruction together or as the soldiers would say, “had seen the elephant”, may have formed a post-war bond of comradeship that was unbreakable until death. After Petersburg, the black battle flags of the black regiments began to fill up with more place names. General Charles Jackson Paine’s colored division of the XVIII Corps and General William Birney’s Colored Brigade of X Corps, about 10,000 total strength, were actively engaged at Chaffin’s Farm, Virginia, on September 29, 1864.

The battle was the result of the Union Army’s attempt to prevent Confederate reinforcements from being sent to support General Jubal Early in the Shenandoah Valley. It was also intended to weaken the Confederate garrison at Petersburg. On the previous night, the Union XVIII Corps crossed a pontoon bridge with the object of proceeding up the Varina Road and capturing the enemy’s defensive works at Chaffin’s Bluff. As soon as the fighting started in earnest, the casualties came in staggering numbers because advances had to be made across swamps and open fields. The black regiments that participated at Chaffin’s Farm and the next day’s battle at New Market Heights were conspicuous in their gallantry.

Here also, the black regiments of the 4th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 22nd, 45th and 127th USCT were filled with Camden County men. The 4th, 7th and 9th USCT, although formed in Maryland were comprised of many Camden County men. Henry Monroe and Thomas Pinkett, both of the 4th USCT, were residents of Lawnside after the War as were John Dennis, Isaac Dingle, George Hinson, Solomon Hubert and Charles and James Robinson, of the 7th USCT. Others from Lawnside, Joseph Brewster. William H. Green, Isaiah Grose, William Jackson, John L. Stephens and Charles A. Still, all participated with their regiments in that terrible bloody battle.

Because casualty statistics were so great during the Civil War and record-keeping so poorly organized, we must rely mainly on numbers of dead instead of names to indicate the severity of our nation’s losses. Gravesites in Camden County tell us only about those who survived the conflict and returned home; thousands were buried where they fell. A review of published lists of those who went to War would lead one to the conclusion that many black soldiers never returned and were part of the large casualty statistics. The May 4, 1864, edition of the West Jersey Press listed names of Thomas Henry, Isaac Butler, James Hitch, William Harris,Wales Taler and Henry Warner, of Stockton Township; Joseph Murray, of Delaware Township; and Isaac Jackson, Martin Haney, James Moulding, James Harris, James Thomas, Josiah Daniel, Joshua .Woolford, Theodore Williams, George Murray , Garrett Patton and James Walin from Centre Township as inductees.

Newton Township provided James Morris, William Conner, George Robinson, Jesse Boldin, John Thomas and Eli Mott. No Camden County cemetery record can be found which indicates where any of these men are buried, with the single exception of Garrett Patton. Patton was a Landsman in the U.S. Navy and is interred at Mt. Zion Cemetery, Lawnside. Other names which appeared in the West Jersey Press (August 16, 1864), included William James, James Johnson, John Johnson, William Jewliss, Israel Jordan, Pernell Johnson, William H. Jones, Isaac Jerman and Jersey Jones. State War records show that James Johnson survived as a member of the 22nd USCT and that William H. Jones of the 8th USCT came home as well. Shortly before the end of the War the West Jersey Press printed a list of drafted men by county. On March 1,1865 the names from Camden City’s Middle Ward appeared, Robert Winay and Peter Pousell. The latter name undoubtedly refers to Peter M.D. Postles, 2nd U.S. Colored Cavalry, later to become Camden County’s first black freeholder in 1880.

Listed from Newton Township were: Isaac Wright, Henry Hammon, Robert Monroe, Benjamin Tucker, Charles Brown, Duncon Johnson, Harrison Stephens, Samuel Dyson, Rythhurn Smith, John Powards, Ezekial Byard, David Jones, William Houston, John Long, Reuben Batten, James Smith, George Dehl, Isaac Pageson, Henry Burward, Thomas Smith and Silvier Jefferson. Also from Newton Township were John Madden, Moses Wilcox, Garrett Richardson, Napoleon Reed, James Wheeler Samuel Moire Harvey Peyton and Sheppard Pitts. The only members of this group whose gravesites have been located are Sheppard Pitts and Charles Brown. Delaware Township (Cherry Hill) was home to Samuel Green and Richard Why, Gloucester Township to George Thomas. While we cannot be sure how many survived the War we do know that they all performed their duties as soldiers.

Others who also gave good service included members of the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry at Darbytown Road, Virginia, on October 27, 1864; two colored brigades including regiments from the Philadelphia area which took part in the battle of Nashville, Tennessee on December 15, 1864; and the 13th USCT. This troop lost 221 men in its assault on Overton Hill, which was the greatest regimental loss of the battle. At Honey Hill, South Carolina, on November 30, 1864, the 55th Massachusetts, an all black-regiment, had the highest losses of the battle.

Black regiments were also prominently engaged in the battles of Morris Island, South Carolina; Yazoo City, Mississippi; Poison Springs’ Arkansas; Saline River, Arkansas; Morganza, Louisiana; Tupelo, Mississippi; Burmuda Hundred, Virginia; Darbytown Road,Virginia; Saltville, Virginia; Cox’s Bridge, North Carolina; Spanish Fort, Alabama; James Island, South Carolina; Pleasant Hill, Louisiana; Camden, Arkansas; Fort Pillow, Tennessee; Jacksonville, Florida; Athens, Alabama; Dutch Gap, Virginia; Hatcher’s Run, Virginia; Deveaux Neck, South Carolina; Fort Fisher, North Carolina; the fall of Richmond; Liverpool Heights, Mississippi Prairie D’Ann, Arkansas; Natural Bridge, Florida; Brice’s Cross Roads, Mississippi; Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia; Boykin’s Mills, South Carolina; Wilmington, North Carolina; Chattanooga, Tennessee; Cold Harbor,Virginia; Deep Bottom, Virginia; Malvern Hill, Virginia; Fair Oaks, Virginia; New Market Heights, Virginia; and Wilson’s Wharf; Fillmore; Town Creek; Warsaw; Fort Taylor; Cedar Keys; Bryant’s Plantation; Marion County; Sugar Loaf Hill; Williamsburg; Fort Burnham; Plymouth; Ashepoo River; Federal Point; Sherman’s March through Georgia and Appomattox Court House where General Robert E. Lee was forced to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865.

The surrender of Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia was certainly one of the greatest events of the War. Many black regiments participated and Camden County black soldiers were among them. John Dennis was there with the 7th USCT; Daniel Derry was there with the 8th USCT; Warner Gibbs was there with the l9th USCT; Samuel Grisden was there with the 41st USCT; Timothy Shaw and Cubit Moore were there with the 43rd USCT; Charles A. Still was there with the 4Sth USCT; and John Berry and Handy West were there with the 127th USCT.

The casualty lists of the USCT justify the words inscribed on the battle flag of the 24th Regiment, United States Colored Troops, “FIAT JUSTITIA”, Let Justice Be Done. Of the 449 engagements in which black regiments fought, the casualties were approximately 36,847.” Of those regiments formed at Camp William Penn, the 6th USCT suffered a loss of 211 men; the 8th USCT lost 251 men; the 22nd USCT lost 217 men; the 32nd USCT, 150 men and the 43rd USCT 239 men.

Of the black fighting units which maintained their state designation, the 29th Connecticut suffered 201 casualties; the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, 123 casualties; the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, 270 casualties; and the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, 197 casualties. By the end of the War, the XXV Corps was made up entirely of black soldiers, the largest black military unit ever activated. An additional 250,000 blacks supported the cause in a civilian capacity in labor and supply. Clearly, with the American Civil War, and the lifting off of the shackles of slavery, opportunities for advancement of the African – American culture occurred in the Nineteenth Century.

Although the yoke of slavery was cast off in a single burst of humanity, it would take nearly another one hundred years before the Black man was given a chance to take advantage of the opportunities he had earned during the Civil War. The rumblings of the 1950’s reached a crescendo in the 1960’s, but for those who had fought for these rights it was a hundred years too late. Accolades were cast upon the gallant black troops by their commanding officers too numerous to mention. Colonel Thomas Morgan, described the black troops at the Battle of Nashville, in words appropriate to their role in the War: “Colored soldiers had fought side by side with white troops. They had mingled together in the charge. They had supported each other. They had assisted each other from the field when wounded, and they lay side by side in death. The survivors rejoiced together over a hard fought field, won by common valor. All who witnessed their conduct gave them equal praise. The day we longed to see had come and gone, and the sun went down upon a record of coolness, bravery, manliness, never to be unmade. A new chapter in the history of liberty had been written. It had been shown that marching under the flag of freedom, animated by a love of liberty, even the slave becomes a man and a hero.”(see 97)

An officer on General Sherman’s staff in Georgia remarked about black troops after the surrender of General Joseph Johnston’s army on April 26, 1865: ” During our stay in Raleigh I witnessed a scene which to me was one of the most impressive of the war.” It was the review by General Sherman of a division of colored troops. These troops passed through the principal streets of the city. They were well drilled, dressed in new and handsome uniforms, and with their bright bayonets gleaming in the sun they made a splendid appearance. The sides of the streets were lined with residents of the city and the surrounding country, — many of them, I presume, the former owners of some of these soldiers. (see 98)

General Benjamin F. Butler, may have said it best when he bade farewell to the black men who served under him: “In this army you have been treated as soldiers, not as laborers. You have shown yourself worthy of the uniform you wear. The best officers of the Union seek to command you. Your bravery has won the admiration of those who would be your masters. Your patriotism, fidelity and courage have illustrated the best qualities of manhood. With the bayonet you have unlocked the iron barred gates of prejudice, and | opened the new fields of freedom, liberty and equality of right to yourselves and to your race.”(see 99)

Sixteen Congressional Medals of Honor for bravery above and beyond the call of duty were awarded to black soldiers during the Civil War. The slave had come a long way. “The Southern position that slaves could not bear arms was essentially correct: a slave was not a man. The war ended slavery. The Negro soldier proved that the slave could become a man.” (see 100)